Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species Human

| Homo ("humans") Temporal range: Piacenzian-Present, | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Guild: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family unit: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Type species | |

| Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| Species | |

other species or subspecies suggested | |

| Synonyms | |

| Synonyms

| |

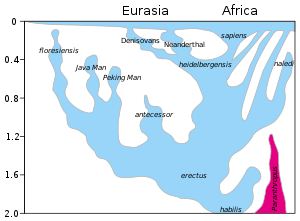

Overview of speciation and hybridization within the genus Homo over the last 2 meg years (vertical axis). The rapid "Out of Africa" expansion of H. sapiens is indicated at the peak of the diagram, with admixture indicated with Neanderthals, Denisovans, and unspecified primitive African hominins.

Man taxonomy is the nomenclature of the homo species (systematic name Homo sapiens, Latin: "wise homo") within zoological taxonomy. The systematic genus, Homo, is designed to include both anatomically mod humans and extinct varieties of archaic humans. Current humans have been designated as subspecies Man sapiens sapiens, differentiated, according to some, from the straight ancestor, Man sapiens idaltu (with some other research instead classifying idaltu and current humans as belonging to the aforementioned subspecies[1] [2] [3]).

Since the introduction of systematic names in the 18th century, noesis of man evolution has increased drastically, and a number of intermediate taxa have been proposed in the 20th and early on 21st centuries. The most widely accepted taxonomy grouping takes the genus Man equally originating betwixt 2 and three million years ago, divided into at least 2 species, archaic Human being erectus and modern Human sapiens, with almost a dozen farther suggestions for species without universal recognition.

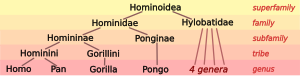

The genus Human being is placed in the tribe Hominini alongside Pan (chimpanzees). The two genera are estimated to have diverged over an extended fourth dimension of hybridization spanning roughly 10 to half-dozen million years ago, with possible admixture every bit tardily as 4 one thousand thousand years ago. A subtribe of uncertain validity, group archaic "pre-human" or "para-human" species younger than the Man-Pan split, is Australopithecina (proposed in 1939).

A proposal by Wood and Richmond (2000) would innovate Hominina as a subtribe alongside Australopithecina, with Man the but known genus within Hominina. Alternatively, following Cela-Conde and Ayala (2003), the "pre-man" or "proto-human" genera of Australopithecus, Ardipithecus, Praeanthropus, and possibly Sahelanthropus, may be placed on equal footing alongside the genus Man. An even more radical view rejects the sectionalisation of Pan and Homo as separate genera, which based on the Principle of Priority would imply the reclassification of chimpanzees every bit Homo paniscus (or similar).[4]

Categorizing humans based on phenotypes is a socially controversial subject field. Biologists originally classified races every bit subspecies, only contemporary anthropologists reject the concept of race as a useful tool to understanding humanity, and instead view humanity as a complex, interrelated genetic continuum. Taxonomy of the hominins continues to evolve.[five] [6]

History [edit]

Human taxonomy on one mitt involves the placement of humans within the taxonomy of the hominids (dandy apes), and on the other the segmentation of primitive and modern humans into species and, if applicative, subspecies. Modern zoological taxonomy was developed by Carl Linnaeus during the 1730s to 1750s. He named the human species as Homo sapiens in 1758, as the but fellow member species of the genus Homo, divided into several subspecies corresponding to the corking races. The Latin noun homō (genitive hominis) means "human being". The systematic proper noun Hominidae for the family of the great apes was introduced by John Edward Gray (1825).[7] Greyness also supplied Hominini as the proper noun of the tribe including both chimpanzees (genus Pan) and humans (genus Homo).

The discovery of the first extinct archaic human species from the fossil record dates to the mid 19th century: Homo neanderthalensis, classified in 1864. Since then, a number of other archaic species have been named, only in that location is no universal consensus as to their exact number. After the discovery of H. neanderthalensis, which even if "archaic" is recognizable as clearly human, tardily 19th to early 20th century anthropology for a time was occupied with finding the supposedly "missing link" between Homo and Pan. The "Piltdown Man" hoax of 1912 was the fraudulent presentation of such a transitional species. Since the mid-20th century, knowledge of the development of Hominini has become much more detailed, and taxonomical terminology has been altered a number of times to reverberate this.

The introduction of Australopithecus as a third genus, alongside Human and Pan, in the tribe Hominini is due to Raymond Sprint (1925). Australopithecina as a subtribe containing Australopithecus too as Paranthropus (Broom 1938) is a proposal by Gregory & Hellman (1939). More recently proposed additions to the Australopithecina subtribe include Ardipithecus (1995) and Kenyanthropus (2001). The position of Sahelanthropus (2002) relative to Australopithecina within Hominini is unclear. Cela-Conde and Ayala (2003) advise the recognition of Australopithecus, Ardipithecus, Praeanthropus, and Sahelanthropus (the latter incertae sedis) as separate genera.[viii]

Other proposed genera, now mostly considered function of Homo, include: Pithecanthropus (Dubois, 1894), Protanthropus (Haeckel, 1895), Sinanthropus (Black, 1927), Cyphanthropus (Pycraft, 1928) Africanthropus (Dreyer, 1935),[9] Telanthropus (Broom & Anderson 1949), Atlanthropus (Arambourg, 1954), Tchadanthropus (Coppens, 1965).

The genus Human being has been taken to originate some two meg years agone, since the discovery of stone tools in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, in the 1960s. Homo habilis (Leakey et al., 1964) would be the first "human" species (member of genus Homo) by definition, its type specimen being the OH seven fossils. However, the discovery of more fossils of this type has opened upwardly the argue on the delineation of H. habilis from Australopithecus. Especially, the LD 350-one jawbone fossil discovered in 2013, dated to 2.8 Mya, has been argued as being transitional between the two.[10] It is as well disputed whether H. habilis was the offset hominin to use stone tools, as Australopithecus garhi, dated to c. 2.five Mya, has been found along with rock tool implements.[11] Fossil KNM-ER 1470 (discovered in 1972, designated Pithecanthropus rudolfensis by Alekseyev 1978) is now seen as either a third early species of Homo (alongside H. habilis and H. erectus) at about two million years ago, or alternatively every bit transitional betwixt Australopithecus and Homo.[12]

Wood and Richmond (2000) proposed that Gray's tribe Hominini ("hominins") exist designated as comprising all species afterward the chimpanzee-human terminal common antecedent past definition, to the inclusion of Australopithecines and other possible pre-human being or para-homo species (such as Ardipithecus and Sahelanthropus) not known in Grey's time.[13] In this proposition, the new subtribe of Hominina was to exist designated as including the genus Homo exclusively, so that Hominini would have two subtribes, Australopithecina and Hominina, with the only known genus in Hominina existence Homo. Orrorin (2001) has been proposed as a possible ancestor of Hominina but not Australopithecina.[xiv]

Designations alternative to Hominina accept been proposed: Australopithecinae (Gregory & Hellman 1939) and Preanthropinae (Cela-Conde & Altaba 2002);[xv]

Species [edit]

At least a dozen species of Human other than Homo sapiens take been proposed, with varying degrees of consensus. Homo erectus is widely recognized as the species directly bequeathed to Man sapiens.[ commendation needed ] Nigh other proposed species are proposed as alternatively belonging to either Homo erectus or Homo sapiens as a subspecies. This concerns Human ergaster in item.[16] [17] Ane proposal divides Homo erectus into an African and an Asian variety; the African is Homo ergaster, and the Asian is Human being erectus sensu stricto. (Inclusion of Homo ergaster with Asian Homo erectus is Human being erectus sensu lato.)[18] There appears to be a recent tendency, with the availability of ever more difficult-to-classify fossils such as the Dmanisi skulls (2013) or Human being naledi fossils (2015) to subsume all primitive varieties under Homo erectus.[xix] [20] [21]

| Lineages | Temporal range (kya) | Habitat | Developed summit | Developed mass | Cranial capacity (cmiii) | Fossil record | Discovery/ publication of name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. habilis membership in Man uncertain | 2,100–one,500[a] [b] | Tanzania | 110–140 cm (3 ft 7 in – four ft 7 in) | 33–55 kg (73–121 lb) | 510–660 | Many | 1960 1964 |

| H. rudolfensis membership in Homo uncertain | ane,900 | Republic of kenya | 700 | two sites | 1972 1986 | ||

| H. gautengensis besides classified as H. habilis | 1,900–600 | South Africa | 100 cm (3 ft 3 in) | 3 individuals[24] [c] | 2010 2010 | ||

| H. erectus | 1,900–140[25] [d] [26] [e] | Africa, Eurasia | 180 cm (5 ft eleven in) | lx kg (130 lb) | 850 (early) – i,100 (late) | Many[f] [g] | 1891 1892 |

| H. ergaster African H. erectus | 1,800–1,300[28] | East and Southern Africa | 700–850 | Many | 1949 1975 | ||

| H. antecessor | 1,200–800 | Western Europe | 175 cm (5 ft 9 in) | xc kg (200 lb) | ane,000 | 2 sites | 1994 1997 |

| H. heidelbergensis early on H. neanderthalensis | 600–300[h] | Europe, Africa | 180 cm (v ft 11 in) | ninety kg (200 lb) | 1,100–1,400 | Many | 1907 1908 |

| H. cepranensis a unmarried fossil, peradventure H. heidelbergensis | c. 450[29] | Italy | 1,000 | 1 skull cap | 1994 2003 | ||

| H. longi | 309–138[xxx] | Northeast Cathay | 1,420[31] | one individual | 1933 2021 | ||

| H. rhodesiensis early on H. sapiens | c. 300 | Zambia | i,300 | Single or very few | 1921 1921 | ||

| H. naledi | c. 300[32] | Southward Africa | 150 cm (iv ft xi in) | 45 kg (99 lb) | 450 | xv individuals | 2013 2015 |

| H. sapiens (anatomically modernistic humans) | c. 300–present[i] | Worldwide | 150–190 cm (4 ft 11 in – half-dozen ft iii in) | 50–100 kg (110–220 lb) | 950–1,800 | (extant) | —— 1758 |

| H. neanderthalensis | 240–40[35] [j] | Europe, Western Asia | 170 cm (5 ft 7 in) | 55–70 kg (121–154 lb) (heavily built) | one,200–i,900 | Many | 1829 1864 |

| H. floresiensis classification uncertain | 190–50 | Indonesia | 100 cm (3 ft 3 in) | 25 kg (55 lb) | 400 | 7 individuals | 2003 2004 |

| Nesher Ramla Man classification uncertain | 140–120 | Israel | several individuals | 2021 | |||

| H. tsaichangensis possibly H. erectus or Denisova | c. 100[k] | Taiwan | 1 individual | 2008(?) 2015 | |||

| H. luzonensis | c. 67[38] [39] | Philippines | three individuals | 2007 2019 | |||

| Denisova hominin | 40 | Siberia | 2 sites | 2000 2010[l] | |||

| Reddish Deer Cave people possible H. sapiens subspecies or hybrid | 15–12[m] [40] | Southwest China | Very few |

Subspecies [edit]

Man sapiens subspecies [edit]

1737 painting of Carl von Linné wearing a traditional Sami costume. Linnaeus is sometimes named as the lectotype of both H. sapiens and H. south. sapiens.[41]

The recognition or nonrecognition of subspecies of Human sapiens has a complicated history. The rank of subspecies in zoology is introduced for convenience, and not by objective criteria, based on pragmatic consideration of factors such as geographic isolation and sexual selection. The informal taxonomic rank of race is variously considered equivalent or subordinate to the rank of subspecies, and the partition of anatomically modern humans (H. sapiens) into subspecies is closely tied to the recognition of major racial groupings based on human genetic variation.

A subspecies cannot be recognized independently: a species will either be recognized as having no subspecies at all or at least two (including whatsoever that are extinct). Therefore, the designation of an extant subspecies Human sapiens sapiens merely makes sense if at to the lowest degree one other subspecies is recognized. H. south. sapiens is attributed to "Linnaeus (1758)" by the taxonomic Principle of Coordination.[42] During the 19th to mid-20th century, it was common exercise to allocate the major divisions of extant H. sapiens as subspecies, post-obit Linnaeus (1758), who had recognized H. s. americanus, H. south. europaeus, H. due south. asiaticus and H. s. afer as grouping the native populations of the Americas, West Eurasia, Eastward Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, respectively. Linnaeus likewise included H. due south. ferus, for the "wild" class which he identified with feral children, and two other "wild" forms for reported specimens now considered very dubious (see cryptozoology), H. s. monstrosus and H. s. troglodytes.[43]

In that location were variations and additions to the categories of Linnaeus, such as H. s. tasmanianus for the native population of Australia.[44] Bory de St. Vincent in his Essai sur fifty'Homme (1825) extended Linné's "racial" categories to every bit many as fifteen: Leiotrichi ("smooth-haired"): japeticus (with subraces), arabicus, indicus, scythicus, sinicus, hyperboreus, neptunianus, australasicus, columbicus, americanus, patagonicus; Oulotrichi ("crisp-haired"): aethiopicus, cafer, hottentotus, melaninus.[45] Similarly, Georges Vacher de Lapouge (1899) as well had categories based on race, such every bit priscus, spelaeus (etc.).

Homo sapiens neanderthalensis was proposed by King (1864) as an culling to Man neanderthalensis.[46] In that location have been "taxonomic wars" over whether Neanderthals were a split species since their discovery in the 1860s. Pääbo (2014) frames this equally a contend that is unresolvable in principle, "since in that location is no definition of species perfectly describing the case."[47] Louis Lartet (1869) proposed Homo sapiens fossilis based on the Cro-Magnon fossils.

There are a number of proposals of extinct varieties of Man sapiens made in the 20th century. Many of the original proposals were not using explicit trinomial classification, fifty-fifty though they are even so cited every bit valid synonyms of H. sapiens by Wilson & Reeder (2005).[48] These include: Human grimaldii (Lapouge, 1906), Homo aurignacensis hauseri (Klaatsch & Hauser, 1910), Notanthropus eurafricanus (Sergi, 1911), Homo fossilis infrasp. proto-aethiopicus (Giuffrida-Ruggeri, 1915), Telanthropus capensis (Broom, 1917),[49] Homo wadjakensis (Dubois, 1921), Man sapiens cro-magnonensis, Homo sapiens grimaldiensis (Gregory, 1921), Human being drennani (Kleinschmidt, 1931),[l] Human galilensis (Joleaud, 1931) = Paleanthropus palestinus (McCown & Keith, 1932).[51] Rightmire (1983) proposed Man sapiens rhodesiensis.[52]

By the 1980s, the practise of dividing extant populations of Homo sapiens into subspecies declined. An early authority explicitly avoiding the sectionalisation of H. sapiens into subspecies was Grzimeks Tierleben, published 1967–1972.[53] A belatedly case of an academic potency proposing that the human racial groups should be considered taxonomical subspecies is John Baker (1974).[54] The trinomial nomenclature Man sapiens sapiens became pop for "mod humans" in the context of Neanderthals beingness considered a subspecies of H. sapiens in the 2d half of the 20th century. Derived from the convention, widespread in the 1980s, of considering two subspecies, H. s. neanderthalensis and H. southward. sapiens, the explicit claim that "H. s. sapiens is the only extant human subspecies" appears in the early 1990s.[55]

Since the 2000s, the extinct Homo sapiens idaltu (White et al., 2003) has gained broad recognition as a subspecies of Homo sapiens, but even in this case there is a dissenting view arguing that "the skulls may not be distinctive plenty to warrant a new subspecies proper name".[56] H. s. neanderthalensis and H. s. rhodesiensis go on to be considered dissever species by some authorities, only the 2010s discovery of genetic evidence of archaic human admixture with modern humans has reopened the details of taxonomy of primitive humans.[57]

Man erectus subspecies [edit]

Man erectus since its introduction in 1892 has been divided into numerous subspecies, many of them formerly considered individual species of Human. None of these subspecies have universal consensus amid paleontologists.

- Human erectus erectus (Coffee Homo) (1970s)[58]

- Man erectus yuanmouensis (Yuanmou Man) (Li et al., 1977)

- Homo erectus lantianensis (Lantian Man) (Woo Ju-Kang, 1964)

- Homo erectus nankinensis (Nanjing Human) (1993)

- Homo erectus pekinensis (Peking Human) (1970s)[58]

- Human being erectus palaeojavanicus (Meganthropus) (Tyler, 2001)

- Human being erectus soloensis (Solo Man) (Oppenoorth, 1932)

- Homo erectus tautavelensis (Tautavel Human) (de Lumley and de Lumley, 1971)

- Human being erectus georgicus (1991)

- Human erectus bilzingslebenensis (Vlček, 2002)[59]

See also [edit]

- Names for the human species

- Timeline of human evolution

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ Confirmed H. habilis fossils are dated to between 2.1 and ane.5 1000000 years ago. This date range overlaps with the emergence of Human erectus.[22] [23]

- ^ Hominins with "proto-Homo" traits may have lived as early as two.viii million years agone, as suggested by a fossil jawbone classified equally transitional between Australopithecus and Homo discovered in 2015.

- ^ A species proposed in 2010 based on the fossil remains of three individuals dated between 1.9 and 0.6 million years ago. The same fossils were too classified equally H. habilis, H. ergaster or Australopithecus by other anthropologists.

- ^ H. erectus may have appeared some two 1000000 years ago. Fossils dated to as much as i.eight million years ago take been found both in Africa and in Southeast Asia, and the oldest fossils by a narrow margin (i.85 to 1.77 meg years ago) were found in the Caucasus, so that it is unclear whether H. erectus emerged in Africa and migrated to Eurasia, or if, conversely, it evolved in Eurasia and migrated dorsum to Africa.

- ^ Homo erectus soloensis, found in Java, is considered the latest known survival of H. erectus. Formerly dated to as belatedly as l,000 to 40,000 years ago, a 2011 study pushed dorsum the date of its extinction of H. e. soloensis to 143,000 years ago at the latest, more likely before 550,000 years agone. [27]

- ^ Now also included in H. erectus are Peking Man (formerly Sinanthropus pekinensis) and Java Man (formerly Pithecanthropus erectus).

- ^ H. erectus is now grouped into diverse subspecies, including Man erectus erectus, Homo erectus yuanmouensis, Homo erectus lantianensis, Homo erectus nankinensis, Homo erectus pekinensis, Man erectus palaeojavanicus, Human erectus soloensis, Man erectus tautavelensis, Homo erectus georgicus. The distinction from descendant species such equally Human ergaster, Homo floresiensis, Man antecessor, Homo heidelbergensis and indeed Man sapiens is not entirely clear.

- ^ The type fossil is Mauer 1, dated to ca. 0.6 million years ago. The transition from H. heidelbergensis to H. neanderthalensis between 300 and 243 thousand years ago is conventional, and makes use of the fact that there is no known fossil in this flow. Examples of H. heidelbergensis are fossils found at Bilzingsleben (also classified as Homo erectus bilzingslebensis).

- ^ The age of H. sapiens has long been assumed to be close to 200,000 years, but since 2017 at that place have been a number of suggestions extending this time to every bit high as 300,000 years. In 2017, fossils plant in Jebel Irhoud (Kingdom of morocco) suggest that Human sapiens may have speciated by as early every bit 315,000 years ago.[33] Genetic evidence has been adduced for an age of roughly 270,000 years.[34]

- ^ The starting time humans with "proto-Neanderthal traits" lived in Eurasia as early equally 0.6 to 0.35 million years ago (classified as H. heidelbergensis, as well called a chronospecies considering it represents a chronological grouping rather than being based on clear morphological distinctions from either H. erectus or H. neanderthalensis). There is a fossil gap in Europe between 300 and 243 kya, and by convention, fossils younger than 243 kya are called "Neanderthal".[36]

- ^ younger than 450 kya, either between 190–130 or between 70–10 kya[37]

- ^ conditional names Homo sp. Altai or Homo sapiens ssp. Denisova.

- ^ Bølling–Allerød warming period

References [edit]

- ^ Stringer, Chris (June 12, 2003). "Homo evolution: Out of Ethiopia". Nature. 423 (6941): 693–695. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..692S. doi:10.1038/423692a. PMID 12802315. S2CID 26693109.

- ^ "Herto skulls (Human sapiens idaltu)". talkorigins org. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ Stringer, C. (2016). "The origin and development of Homo sapiens". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Social club of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1698): 20150237. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0237. PMC4920294. PMID 27298468.

- ^ Jared Diamond in The Third Chimpanzee (1991), and Morris Goodman (2003) Hecht, Jeff (19 May 2003). "Chimps are human, gene study implies". New Scientist . Retrieved 2011-12-08 .

- ^ 1000. Wagner, Jennifer (2016). "Anthropologists' views on race, ancestry, and genetics". American Journal of Concrete Anthropology. 162 (ii): 318–327. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23120. PMC5299519. PMID 27874171.

- ^ "AAA Statement on Race". American Anthropological Association.

- ^ J. Due east. Gray, "An outline of an attempt at the disposition of Mammalia into Tribes and Families, with a list of genera apparently appertaining to each Tribe", Register of Philosophy, new series (1825), pp. 337–344.

- ^ Cela-Conde, C. J.; Ayala, F. J. (2003). "Genera of the human lineage". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences. 100 (13): 7684–7689. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.7684C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0832372100. PMC164648. PMID 12794185.

- ^ Introduced for the Florisbad Skull (discovered in 1932, Homo florisbadensis or Human being helmei). Also the genus suggested for a number of archaic human skulls found at Lake Eyasi past Weinert (1938). Leaky, Periodical of the East Africa Natural History Club (1942), p. 43.

- ^ Villmoare, B. (2015). "Early on Homo at ii.eight Ma from Ledi-Geraru, Distant, Ethiopia". Science. 347 (6228): 1352–1355. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1352V. doi:10.1126/scientific discipline.aaa1343. PMID 25739410. . Some paleoanthropologists regard the H. habilis taxon as invalid, made up of fossil specimens of Australopithecus and Homo. Tattersall, I. & Schwartz, J.H., Extinct Humans, Westview Press, New York, 2001, p. 111.

- ^ De Heinzelin, J; Clark, JD; White, T; Hart, W; Renne, P; Woldegabriel, G; Beyene, Y; Vrba, Eastward (1999). "Environs and behavior of two.5-million-twelvemonth-sometime Bouri hominids". Science. 284 (5414): 625–9. Bibcode:1999Sci...284..625D. doi:ten.1126/science.284.5414.625. PMID 10213682.

- ^ Kaplan, Matt (eight Baronial 2012). "Fossils point to a large family for man ancestors". Nature . Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ Wood and Richmond; Richmond, BG (2000). "Human evolution: taxonomy and paleobiology". Journal of Beefcake. 197 (Pt 1): 19–60. doi:ten.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19710019.x. PMC1468107. PMID 10999270.

- ^ Reynolds, Sally C; Gallagher, Andrew (2012-03-29). African Genesis: Perspectives on Hominin Evolution. ISBN9781107019959.

- ^ Brunet, Thou.; et al. (2002). "A new hominid from the upper Miocene of Chad, central Africa". Nature. 418 (6894): 145–151. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..145B. doi:10.1038/nature00879. PMID 12110880. S2CID 1316969. Cela-Conde, C.J.; Ayala, F.J. (2003). "Genera of the human being lineage". PNAS. 100 (13): 7684–7689. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.7684C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0832372100. PMC164648. PMID 12794185. Wood, B.; Lonergan, N. (2008). "The hominin fossil record: taxa, grades and clades" (PDF). J. Anat. 212 (four): 354–376. doi:x.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00871.x. PMC2409102. PMID 18380861.

- ^ Hazarika, Manji (16–thirty June 2007). "Man erectus / ergaster and Out of Africa: Recent Developments in Paleoanthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology" (PDF).

- ^ Klein, R. (1999). The Man Career: Human biological and cultural origins . Chicago, IL: Academy of Chicago Press. ISBN0226439631.

- ^ Antón, S.C. (2003). "Natural history of Homo erectus". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 122: 126–170. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10399. PMID 14666536.

Past the 1980s, the growing numbers of H. erectus specimens, especially in Africa, led to the realization that Asian H. erectus (H. erectus sensu stricto), once thought so primitive, was in fact more derived than its African counterparts. These morphological differences were interpreted by some as show that more than ane species might be included in H. erectus sensu lato (due east.g., Stringer, 1984; Andrews, 1984; Tattersall, 1986; Wood, 1984, 1991a, b; Schwartz and Tattersall, 2000) ... Unlike the European lineage, in my opinion, the taxonomic issues surrounding Asian vs. African H. erectus are more intractable. The outcome was most pointedly addressed with the naming of H. ergaster on the ground of the type mandible KNM-ER 992, but also including the partial skeleton and isolated teeth of KNM-ER 803 among other Koobi Fora remains (Groves and Mazak, 1975). Recently, this specific proper noun was applied to almost early African and Georgian H. erectus in recognition of the less-derived nature of these remains vis à vis conditions in Asian H. erectus (see Wood, 1991a, p. 268; Gabunia et al., 2000a). At least portions of the paratype of H. ergaster (east.grand., KNM-ER 1805) are not included in most current conceptions of that taxon. The H. ergaster question remains famously unresolved (eastward.g., Stringer, 1984; Tattersall, 1986; Forest, 1991a, 1994; Rightmire, 1998b; Gabunia et al., 2000a; Schwartz and Tattersall, 2000), in no modest function because the original diagnosis provided no comparison with the Asian fossil record.

- ^ "Skull suggests three early human species were one". News & Comment. Nature.

- ^ Lordkipanidze, David; Ponce de Leòn, Marcia Southward.; Margvelashvili, Ann; Rak, Yoel; Rightmire, Grand. Philip; Vekua, Abesalom; Zollikofer, Christoph P. East. (xviii Oct 2013). "A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Evolutionary Biology of Early on Human". Science. 342 (6156): 326–331. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..326L. doi:10.1126/science.1238484. PMID 24136960. S2CID 20435482.

- ^ Switek, Brian (17 October 2013). "Cute skull spurs fence on homo history". National Geographic. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ Schrenk F, Kullmer O, Bromage T (2007). "The Primeval Putative Human being Fossils". In Henke Westward, Tattersall I (eds.). Handbook of Paleoanthropology. Vol. 1. In collaboration with Thorolf Hardt. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 1611–1631. doi:10.1007/978-three-540-33761-4_52. ISBN978-3-540-32474-four.

- ^ DiMaggio EN, Campisano CJ, Rowan J, Dupont-Nivet One thousand, Deino AL, Bibi F, et al. (March 2015). "Paleoanthropology. Tardily Pliocene fossiliferous sedimentary record and the environmental context of early Homo from Distant, Ethiopia". Science. 347 (6228): 1355–9. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1355D. doi:ten.1126/science.aaa1415. PMID 25739409. S2CID 43455561.

- ^ Curnoe D (June 2010). "A review of early Man in southern Africa focusing on cranial, mandibular and dental remains, with the clarification of a new species (Homo gautengensis sp. november.)". Homo. 61 (3): 151–77. doi:x.1016/j.jchb.2010.04.002. PMID 20466364.

- ^ Haviland WA, Walrath D, Prins HE, McBride B (2007). Evolution and Prehistory: The Homo Challenge (eighth ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. p. 162. ISBN978-0-495-38190-7.

- ^ Ferring R, Oms O, Agustí J, Berna F, Nioradze M, Shelia T, et al. (June 2011). "Earliest human being occupations at Dmanisi (Georgian Caucasus) dated to 1.85-i.78 Ma". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (26): 10432–6. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10810432F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106638108. PMC3127884. PMID 21646521.

- ^ Indriati Due east, Swisher CC, Lepre C, Quinn RL, Suriyanto RA, Hascaryo AT, et al. (2011). "The age of the 20 meter Solo River terrace, Java, Indonesia and the survival of Homo erectus in Asia". PLOS Ane. 6 (half-dozen): e21562. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621562I. doi:10.1371/periodical.pone.0021562. PMC3126814. PMID 21738710.

- ^ Hazarika M (2007). "Homo erectus/ergaster and Out of Africa: Contempo Developments in Paleoanthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology" (PDF). EAA Summer School eBook. Vol. 1. European Anthropological Association. pp. 35–41.

Intensive Course in Biological Anthrpology, 1st Summer Schoolhouse of the European Anthropological Association, sixteen–xxx June, 2007, Prague, Czech republic

- ^ Muttoni One thousand, Scardia Thousand, Kent DV, Swisher CC, Manzi Yard (2009). "Pleistocene magnetochronology of early hominin sites at Ceprano and Fontana Ranuccio, Italy". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 286 (1–2): 255–268. Bibcode:2009E&PSL.286..255M. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.06.032.

- ^ Ji Q, Wu W, Ji Y, Li Q, Ni X (25 June 2021). "Belatedly Eye Pleistocene Harbin attic represents a new Human being species". The Innovation. 2 (three): 100132. doi:x.1016/j.xinn.2021.100132. PMC8454552. PMID 34557772.

- ^ Ni X, Ji Q, Wu Due west, Shao Q, Ji Y, Zhang C, Liang L, Ge J, Guo Z, Li J, Li Q, Grün R, Stringer C (25 June 2021). "Massive attic from Harbin in northeastern China establishes a new Heart Pleistocene human lineage". The Innovation. 2 (iii): 100130. doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100130. PMC8454562. PMID 34557770.

- ^ Dirks PH, Roberts EM, Hilbert-Wolf H, Kramers JD, Hawks J, Dosseto A, et al. (May 2017). "Human being naledi and associated sediments in the Rising Star Cave, South Africa". eLife. 6: e24231. doi:10.7554/eLife.24231. PMC5423772. PMID 28483040.

- ^ Callaway, Ewan (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens fossil merits rewrites our species' history". Nature. doi:ten.1038/nature.2017.22114. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Posth C, Wißing C, Kitagawa K, Pagani L, van Holstein Fifty, Racimo F, et al. (July 2017). "Deeply divergent archaic mitochondrial genome provides lower time boundary for African cistron flow into Neanderthals". Nature Communications. 8: 16046. Bibcode:2017NatCo...816046P. doi:10.1038/ncomms16046. PMC5500885. PMID 28675384.

- ^ Bischoff JL, Shamp DD, Aramburu A, et al. (March 2003). "The Sima de los Huesos Hominids Date to Beyond U/Thursday Equilibrium (>350 kyr) and Perhaps to 400–500 kyr: New Radiometric Dates". Journal of Archaeological Science. 30 (three): 275–280. doi:10.1006/jasc.2002.0834. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ^ Dean D, Hublin JJ, Holloway R, Ziegler R (May 1998). "On the phylogenetic position of the pre-Neandertal specimen from Reilingen, Germany". Journal of Man Evolution. 34 (5): 485–508. doi:ten.1006/jhev.1998.0214. PMID 9614635.

- ^ Chang CH, Kaifu Y, Takai M, Kono RT, Grün R, Matsu'ura S, et al. (January 2015). "The kickoff archaic Human from Taiwan". Nature Communications. 6: 6037. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.6037C. doi:ten.1038/ncomms7037. PMC4316746. PMID 25625212.

- ^ Détroit F, Mijares As, Corny J, Daver G, Zanolli C, Dizon East, et al. (April 2019). "A new species of Homo from the Late Pleistocene of the Philippines" (PDF). Nature. 568 (7751): 181–186. Bibcode:2019Natur.568..181D. doi:ten.1038/s41586-019-1067-9. PMID 30971845. S2CID 106411053.

- ^ Zimmer C (10 April 2019). "A new human species once lived in this Philippine cave – Archaeologists in Luzon Island have turned upwardly the bones of a distantly related species, Human luzonensis, farther expanding the human being family unit tree". The New York Times . Retrieved x Apr 2019.

- ^ Curnoe D, Xueping J, Herries AI, Kanning B, Taçon PS, Zhende B, et al. (2012). "Human remains from the Pleistocene-Holocene transition of southwest China suggest a circuitous evolutionary history for East Asians". PLOS I. vii (3): e31918. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731918C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031918. PMC3303470. PMID 22431968.

- ^ "equally far as I know, there is no type textile for Homo sapiens. To exist fair to Linnaeus, the practice of setting type specimens aside doesn't seem to take developed until a century or so subsequently." Bob Ralph, "Befitting to type", New Scientist No. 1548 (nineteen February 1987), p. 59.

- ^ "ICZN glossary". International Lawmaking of Zoological Nomenclature. quaternary ed., article 46.1: "Argument of the Principle of Coordination applied to species-group names. A name established for a taxon at either rank in the species group is deemed to have been simultaneously established by the same author for a taxon at the other rank in the grouping; both nominal taxa have the same name-bearing type, whether that type was fixed originally or afterwards." Homo sapiens sapiens is rarely used earlier the 1940s. In 1946, John Wendell Bailey attributes the proper name to Linnaeus (1758) explicitly: "Linnaeus. Syst. Nat. ed. 10, Vol. 1. pp. twenty, 21, 22, lists five races of man, viz: Homo sapiens sapiens (white — Caucasian) [...]", This is a misattribution, just H. s. sapiens has since often been attributed to Linnaeus. In actual fact, Linnaeus, Syst. Nat. ed. ten Vol. i. p. 21 does not have Homo sapiens sapiens, the "white" or "Caucasian" race being instead called Human sapiens Europaeus. This is explicitly pointed out in Bulletin der Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Anthropologie und Ethnologie Volume 21 (1944), p. 18 (arguing not against H. s. sapiens but against "H. s. albus Fifty." proposed by von Eickstedt and Peters): "die europide Rassengruppe, als Subspecies aufgefasst, [würde] Homo sapiens eurpoaeus L. heissen" ("the Europid racial group, considered every bit a subspecies, would be named H. due south. europeaeus Fifty."). See likewise: John R. Bakery, Race, Oxford University Press (1974), 205.

- ^ Linné, Carl von (1758). Systema naturæ. Regnum animale (10 ed.). pp. 18ff.

- ^ Run into e.chiliad. John Wendell Bailey, The Mammals of Virginia (1946), p. 356.; Periodical of Mammalogy 26-27 (1945), p. 359.; J. Desmond Clark (ed.), The Cambridge History of Africa, Cambridge University Press (1982), p. 141 (with references).

- ^ Annals of Philosophy 11, London (1826), p. 71

- ^ Frederick South. Szalay, Eric Delson, Evolutionary History of the Primates (2013), 508

- ^ Pääbo, Svante (2014). Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes. New York: Basic Books. p. 237.

- ^ Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ T. Harrison in: William H. Kimbel, Lawrence B. Martin (eds.), Species, Species Concepts and Primate Evolution (2013), 361.

- ^ M. R. Drennan, "An Australoid Skull from the Cape Flats", The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland and Ireland Vol. 59 (Jul. - December., 1929), 417-427.

- ^ amid other names suggested for fossils subsequently subsumed nether neanderthalensis, come across: Eric Delson, Ian Tattersall, John Van Couvering, Alison S. Brooks, Encyclopedia of Man Development and Prehistory: Second Edition, Routledge (2004).

- ^ Rightmire GP (June 3, 1983). "The Lake Ndutu cranium and early on Human sapiens in Africa". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 61 (ii): 245–54. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330610214. PMID 6410925.

- ^ English translation (1972–1975): Grzimek'south Animal Life Encyclopedia, Volume 11, p. 55.

- ^ John R. Bakery, Race, Oxford University Press (1974).

- ^ "We are the only surviving subspecies of Human being sapiens." Michio Kitahara, The tragedy of evolution: the human brute confronts modern society (1991), p. eleven.

- ^ Stringer, Chris (June 12, 2003). "Human evolution: Out of Ethiopia". Nature. 423 (6941): 692–3, 695. doi:10.1038/423692a. PMID 12802315. S2CID 26693109.

- ^ Hublin, J. J. (2009). "The origin of Neandertals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (38): 16022–7. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10616022H. doi:x.1073/pnas.0904119106. JSTOR 40485013. PMC2752594. PMID 19805257. Harvati, K.; Frost, S.R.; McNulty, K.P. (2004). "Neanderthal taxonomy reconsidered: implications of 3D primate models of intra- and interspecific differences". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.s.a.A. 101 (five): 1147–52. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.1147H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308085100. PMC337021. PMID 14745010. "Man neanderthalensis Rex, 1864". Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Development. Chichester, Due west Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. 2013. pp. 328–331.

- ^ a b In the 1970s a tendency developed to regard the Javanese variety of H. erectus as a subspecies, Homo erectus erectus, with the Chinese variety being referred to as Homo erectus pekinensis. See: Sartono, South. Implications arising from Pithecanthropus Viii In: Paleoanthropology: Morphology and Paleoecology. Russell H. Tuttle (Ed.), p. 328.

- ^ Emanuel Vlček: Der fossile Mensch von Bilzingsleben (= Bilzingsleben. Bd. vi = Beiträge zur Ur- und Frühgeschichte Mitteleuropas 35). Beier & Beran, Langenweißbach 2002.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_taxonomy

0 Response to "Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species Human"

Post a Comment